The cost of a fuse failure is never just the price of the fuse. It is fire risk, destroyed gear, and hours of unplanned downtime that no one has budgeted for.

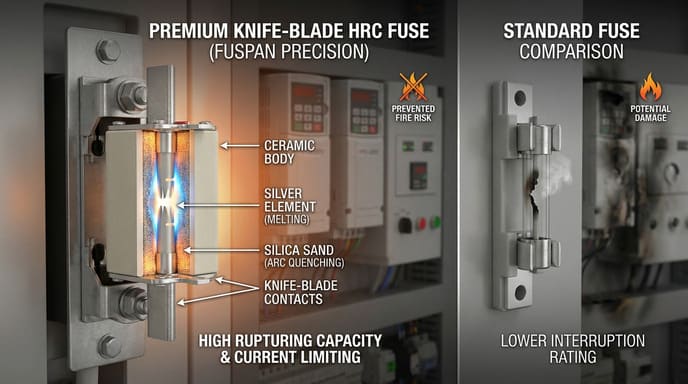

A knife-blade HRC fuse1 is a high-rupturing-capacity, current-limiting fuse with knife contacts that allow fast, safe replacement in low-voltage power distribution, giving predictable disconnection under high fault currents and reducing damage and downtime compared with ordinary fuses or poorly coordinated breakers.

When I talk with a customer about knife-blade HRC fuses, I do not start with curves or catalog codes. I start with the one failure scenario that would keep them awake at night, and I show how the right fuse choice can make that scenario boring and controlled instead of catastrophic.

What is an HRC fuse?

In many projects, people treat fuses as afterthoughts until they see a busbar melted, a panel door warped, or a motor starter completely burned out after a fault. At that moment, “high rupturing capacity” stops being a textbook term and becomes a very expensive lesson.

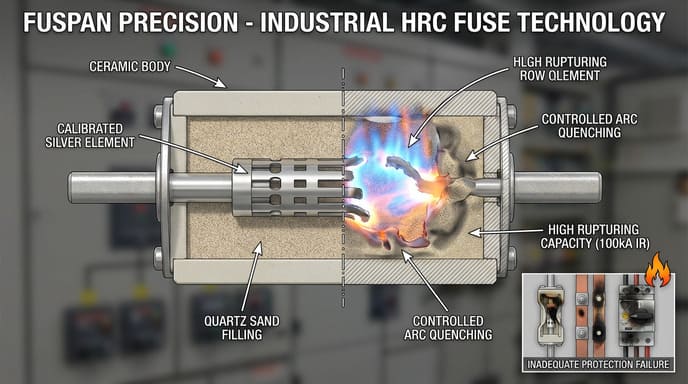

An HRC fuse is a cartridge fuse designed to interrupt very high fault currents safely without exploding or letting dangerous energy pass into downstream equipment. It uses a strong ceramic body, a precisely shaped metal element, and quartz or similar filler to limit current and quench the arc when a fault occurs.

I often explain HRC fuses as “shock absorbers” for fault energy. They have a breaking capacity that can reach tens or even over one hundred kiloamperes, which means they can clear fault currents far above normal operating current without turning the fuse holder into shrapnel. They also have current‑limiting characteristics, so they cut the fault before it reaches its natural peak, which reduces thermal and mechanical stress on cables, contactors, and busbars.

How HRC fuses actually work

During normal operation, current flows through the fuse element without significant heating and the fuse behaves almost invisibly. When a fault occurs, the high current heats and melts the element very quickly, creating an arc inside the body.

The ceramic body and filler material absorb heat and react with the metal vapor to form a high-resistance path, which stretches and extinguishes the arc and forces the current to zero in a controlled way. Because of this construction, HRC fuses can stop extremely high fault currents without bursting and with very stable performance over their service life.

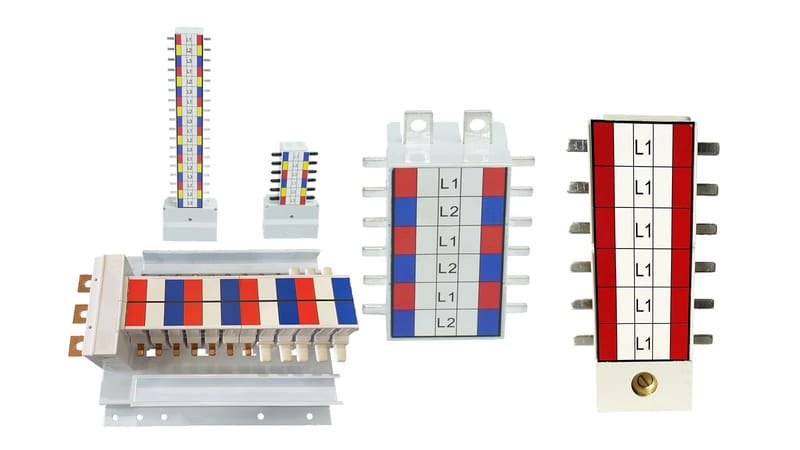

Common HRC fuse formats

| Fuse format | Typical use cases | Mounting style | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH / NT knife-blade HRC | LV distribution, motor control centers, PV DC combiner boxes | Knife blades in fuse bases | High breaking capacity and easy replacement. |

| Cylindrical HRC | Control panels, small loads, electronics auxiliaries | Clip-in or screw-in | Compact and widely standardized. |

| Square-body industrial HRC | Drives, UPS, large transformers, semiconductor protection | Bolted tags | Very high current ratings and specific gR/aR classes. |

In my own projects, once I map these formats to the customer’s actual switchboards and maintenance habits, the discussion moves naturally from “What is HRC?” to “Which HRC format can your team replace safely at 2 a.m. during a shutdown?”.

What is a knife-blade fuse used for?

Many engineers know they need HRC performance, but they underestimate how much the contact format affects safety, replacement speed, and even the risk of future mistakes. This is where the knife-blade style quietly solves problems that one line in the specification sheet never shows.

A knife-blade HRC fuse is mainly used in low-voltage AC and DC distribution panels, motor control centers, inverters, and PV or battery systems where high breaking capacity and quick, tool‑free replacement are both important. The knife blades slide into dedicated fuse bases, which provide strong contact pressure and clear isolation distance when the fuse is removed.

I often see knife-blade HRC fuses in feeder circuits, incoming sections of distribution boards, and PV or battery combiner boxes that must deal with high prospective short-circuit currents but still remain serviceable by plant technicians, not only by external contractors. The knife format also supports use with fuse pullers and extractors, which keeps hands further from live parts and hot components during replacement under pressure.

Why knife-blade format matters

From my point of view, the knife-blade format2 changes the conversation in three ways.

First, it improves mechanical robustness and contact reliability, because the blades engage firmly with spring contacts in the base, which keeps resistance and heating under control even at high currents. Second, it makes isolation very visible: when the fuse is out, there are clearly open blades and a physical gap, which maintenance teams trust more than a small rocker or pushbutton.

Third, it speeds up fault recovery. A technician can open the panel, verify that the system is de‑energized, pull the knife-blade fuse with a proper extractor, insert a new one of the correct rating, and restore supply in minutes if the root cause is clear and safe to re‑energize. In my own work, this ease of replacement often convinces customers to keep spare knife-blade HRC fuses in standardized sizes so they do not improvise with wrong components during emergencies.

Typical knife-blade HRC applications

| Application area | Typical voltage / current | Why knife-blade HRC is used |

|---|---|---|

| LV main incomers and feeders | Up to 500–690 V AC and hundreds of amperes | High breaking capacity and clear disconnection for transformers and busbars. |

| Motor control centers | Large motors and pumps | Coordination with contactors and overload relays, plus quick replacement during production. |

| PV and battery combiner boxes | DC strings and battery racks | Current-limiting protection with robust isolation for DC faults. |

How do you select the right HRC fuse?

When a customer asks me which HRC fuse to use, they often expect a simple current rating answer. However, a number that matches the motor full-load current or cable rating is just the starting point, not the end.

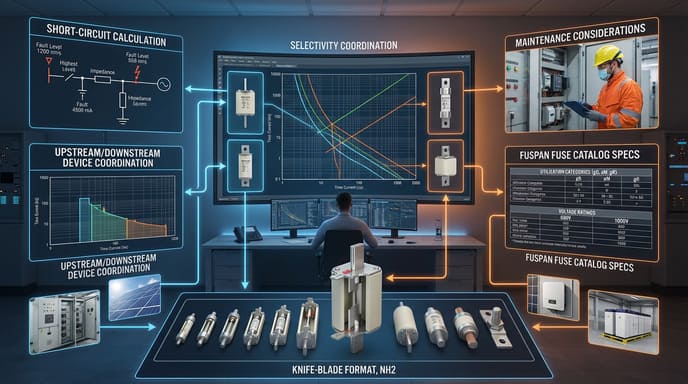

To select the right HRC fuse, I always start with three anchors: coordination with upstream and downstream devices, realistic short‑circuit current at the installation point, and the practical needs of the people who will replace the fuse during a fault. Then I look at standards, utilization category, voltage rating, and physical format to make sure the choice fits both the system design and on‑site habits.

Coordination means that the fuse should protect cables, breakers, contactors, and end devices without causing nuisance operation or leaving gaps in protection. For example, a gG fuse3 in a feeder should back up downstream MCBs without letting too much energy through in case of a severe fault, and the time‑current curves should show clear selectivity wherever possible. I often compare fuse curves with breaker curves during design reviews to show that “correct on paper” is not always “selective in real life”.

Short‑circuit level at the installation point is the second anchor. The HRC fuse must have a breaking capacity above the calculated prospective fault current, with a margin that reflects utility changes and parallel sources like generators or inverters. Many catalogs list breaking capacities up to 80 kA, 100 kA, or even 120 kA for NH/NT and square-body industrial fuses, so there is usually a safe choice if this check is done early.

Practical selection checklist

In my own workflow, I use a simple checklist that links technical choices to maintainability.

| Step | Key question | What I check |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | System voltage and type | AC or DC, rated voltage of the fuse, and standard (IEC/GB). |

| 2 | Load type and utilization | gG/gL for general cables and feeders, aM for motors, aR/gR for semiconductors. |

| 3 | Continuous current and cable size | Fuse rating vs. cable thermal limit and load current, including ambient conditions. |

| 4 | Prospective short‑circuit current | Breaking capacity of the fuse vs. calculated fault current, margin included. |

| 5 | Selectivity and backup with other devices | Time‑current curves vs. upstream breakers and downstream devices. |

| 6 | Physical format and replacement method | Knife-blade vs. cylindrical, matching bases, use of extractors, space in panel. |

By walking customers through this table, I help them see that selecting an HRC fuse is not only about ampere rating. It is about building a protection concept that stays stable even when future staff, future loads, and future grid conditions change.

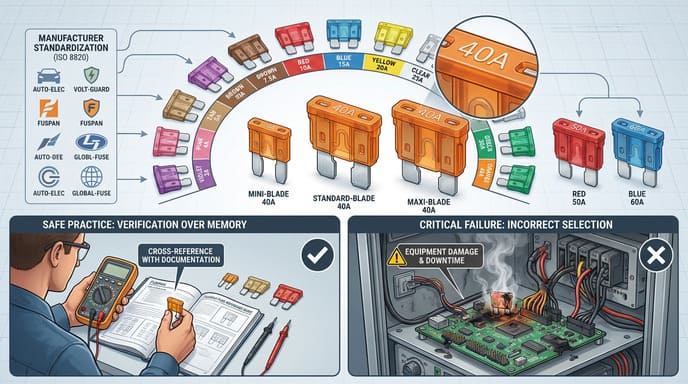

What color is a 40 amp blade fuse?

The question about color often sounds simple and harmless, and that is why it worries me the most. Many teams trust memory instead of documents for something that can cut power to a critical circuit in one second.

In standard automotive and low‑voltage blade fuse systems, a 40 A blade fuse is normally orange across mini, standard, and maxi types, according to common color coding tables. You can see this same mapping in catalogs for orange 40 A ATO or similar blade fuses from multiple suppliers.

I often meet maintenance teams who can name colors and ratings faster than they can read a label, because they swap automotive-style blade fuses all day. This works as long as they stay inside one standard range, but it becomes dangerous when they mix micro, mini, standard, and maxi styles, or when a supplier uses similar colors for different product families. In DC panels and auxiliary circuits around larger HRC knife-blade fuses, this habit can easily lead to a wrong fuse value used “just for testing”.

Safer use of color coding

For this reason, I treat color as a helpful hint, not as the final authority. I always suggest three rules to customers.

First, always confirm the printed ampere value on the fuse body before replacement, even when the color looks familiar. Second, avoid mixing different blade fuse families in the same row of a distribution block unless the documentation and labels are very clear. Third, keep a simple, printed fuse chart in each panel that shows both colors and ratings for the specific fuse types used in that board.

In my own projects, I also try to align DC auxiliary fuse ratings and colors with standard automotive codes when it makes sense, so technicians feel at home but still see clear labels and drawings to fall back on when stress is high. This way, color memory supports safe behavior instead of replacing it.

Conclusion

In my view, a knife-blade HRC fuse is not just a part number. It is a small but critical part of a protection concept that turns high‑fault events into safe, predictable interruptions, and it only works when ratings, formats, and even color codes are chosen with the people under pressure in mind.