I remember the first time I had to pick between a fuse switch disconnector and a molded case circuit breaker. I stood in front of a cabinet with high fault currents, and I had to decide fast. Both devices promised protection, but in different ways. I will share what I learned, with my own stories, so you can make your choice with more confidence.

What a Fuse Switch Disconnector Does for Me

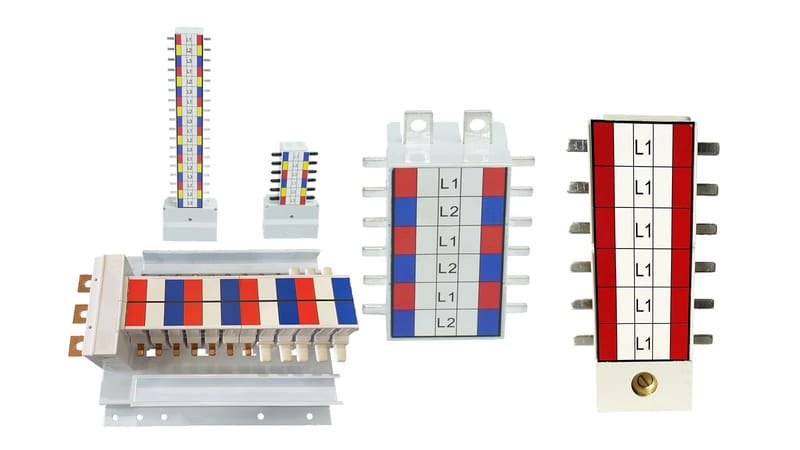

A fuse switch disconnector gives me a manual switch combined with a fuse. It lets me isolate a circuit and protects against overcurrent. I like its simplicity. A fuse can interrupt very high fault currents, up to 200 kA, and it acts in less than a millisecond on high faults. When I protect sensitive equipment, that speed matters.

Pros I Noticed

- High interrupting capacity for very high faults

- Good cost at high currents above 800 A or fault levels above 50 kA

- Simple and rugged, no complex electronics

Cons I Faced

- After a fault I must replace the fuse, so there is downtime and I keep spare fuses

- Fixed trip points, not adjustable for variable loads

- In three-phase, one fuse blowing can cause single-phasing and hurt motors

Living With FSDs

When I ran a line with high fault currents, I chose an FSD because MCCBs rated for 50 kA were too expensive. The fuse links were affordable. I learned to keep a stock of spare fuses on site. I trained the team to swap them safely. I also added a three-pole linked fuse holder to cut single-phasing risk. I checked the fuse curves, like gG or aM, and matched them to motor loads. The fixed nature meant less tuning, but for that line, the simplicity was a relief.

What a Molded Case Circuit Breaker Offers

A molded case circuit breaker uses mechanical parts to protect against overloads and short circuits. It trips on its own and I can reset it. It opens all poles at once, which avoids single-phasing. I use MCCBs when I want adjustable settings and less downtime after trips.

Pros I Value

- Reset after a trip, so less downtime and less maintenance

- Adjustable trip units, thermal and magnetic, to tune to load profiles

- Simultaneous tripping of all poles

- Lower total cost over life despite higher upfront cost

Cons I Saw

- Slightly slower on extremely high fault currents compared to fast fuses

- Very high rating MCCBs can be costly

- More complex, sometimes needs specialized knowledge to install and maintain

Working With MCCBs

In another project, I had a tiered system with selective coordination needs. I chose MCCBs with electronic trip units. I set long delay, short delay, and instantaneous settings to make sure only the right breaker would trip on a fault. The ability to reset saved time. I did notice the response to very high faults was slower than a fuse, but within acceptable limits. I also learned about UL 489 and IEC 60947-2 standards that applied to the breakers I used, and I made sure the certifications matched the market.

Understanding Standards and Certifications

I had to make sure the devices met the right standards. For FSDs, I looked at IEC/EN 60947-3 and IEC 60269. For MCCBs, IEC/EN 60947-2 and UL 489 were key. In North America, UL and CSA marks mattered. In Europe, CE was needed. I checked the tested short-circuit breaking capacities, marked as Icu and Ics, and the isolation function symbols. These details gave me peace of mind.

Reading the Labels

One time, I almost bought a breaker without the right certification for a Canadian site. I learned to read the data plates closely. The breaker needed CSA approval. I also checked the Icu value to ensure it could handle the available fault current. The isolation symbol on an FSD meant I could use it as a disconnect. These small marks became big factors. They kept inspectors happy and kept my projects compliant.

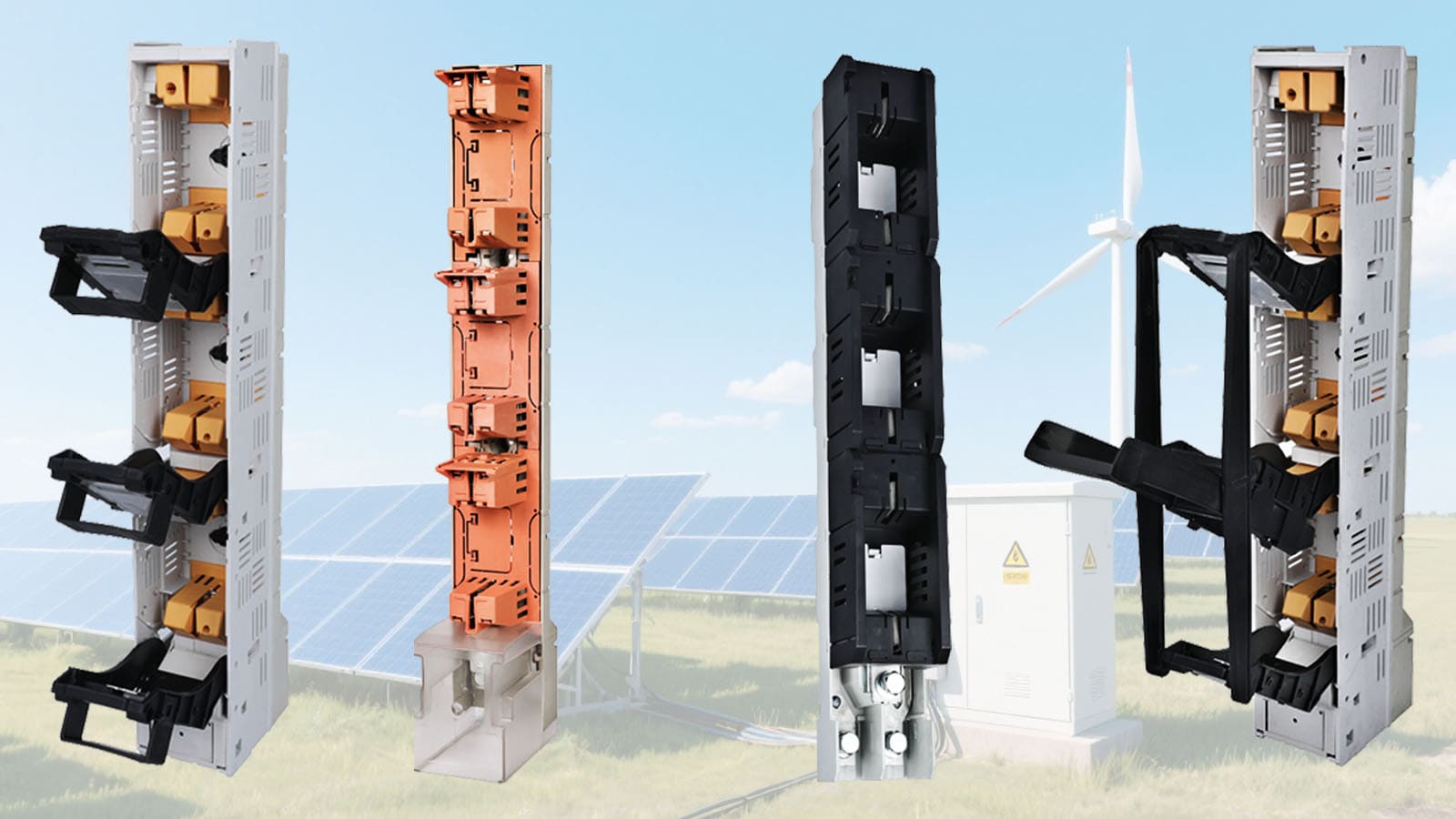

Rated Parameters and Curves

I always look at rated voltage, rated current, number of poles, and breaking capacity. For MCCBs, I see if the trip curve is B, C, or D, and I adjust thermal and magnetic trips. Some models allow ground fault settings. For fuses, I pick gG/gL for general use, aM for motors, or aR for semiconductors. I study the time-current curves to match the protection to the load.

Matching Curves to Loads

In one plant, we had variable speed drives and motors. I chose aM fuses for motor circuits because they handle inrush. For MCCBs feeding drives, I set the instantaneous trip higher to avoid nuisance trips on start. I used the B, C, D curve guides to decide. A C curve suited the mixed loads. I learned that time-current curves are like stories. They tell me when a device will act. I match that story to the behavior of my load.

Selectivity and Cascading

In a layered system, I want only the device closest to the fault to open. MCCBs often come with selectivity tables. They show which combinations will act in order. FSDs with downstream fuses can also coordinate. Cascading, or current limiting, can reduce stress on downstream devices. I plan to avoid both levels tripping at once.

Building a Coordinated System

When I built a distribution board, I used an upstream MCCB and downstream miniature breakers. I checked the selectivity tables to make sure a downstream fault would not trip the main. In another case, I used a high speed fuse upstream of an MCCB to limit fault energy. This helped with arc flash reduction. Planning the cascade saved me from widespread outages when a single circuit failed.

Typical Applications

I pick FSDs for high fault current mains, for sensitive electronics, or where cost at high ratings matters. I pick MCCBs for control panels, HVAC, and motor circuits when I need adjustable protection and quick reset. I think about single-phasing risk for motors with fuses. I think about the need for remote operation or auxiliary contacts with MCCBs.

Choosing for Real Projects

In a metal plant with a 100 kA fault level, I used FSDs on the main feeders. The cost was lower, and the fuses handled the fault. For an office HVAC panel, I used MCCBs because the loads varied and I wanted to adjust settings. In a motor control center, I weighed single-phasing risk, so I used MCCBs with phase failure relays. Each choice was tied to the real risk and the ease of maintenance for my team.

Installation and Maintenance

I install these devices with care. I check ambient temperature, altitude, and IP rating. I choose busbar or cable connections based on the enclosure. I torque terminals to spec. For maintenance, I use thermal imaging to spot hot joints. I manage fuse inventory. I test MCCBs by operating them and doing regular trip tests. I note the mechanical life of MCCBs.

Keeping Systems Healthy

I recall a time when a loose lug caused a hot spot on an MCCB. A thermal camera spotted it during a routine check. We tightened it and avoided a failure. For FSDs, I learned to keep spare gG and aM fuses in stock. When a fuse blew, we replaced it quickly. I also cleaned dust from enclosures to keep IP ratings effective. Simple steps kept the protection devices ready.

Safety and Fault Analysis

Single-phasing is a risk with fuses. I use three-pole linked fuses or phase monitoring relays to reduce that risk. I think about arc flash energy. Current limiting fuses and fast trip settings can lower arc flash. I always do a fault current study to know the stresses.

Managing Risks

In a workshop, a single fuse blew on a motor circuit. The motor ran on two phases and overheated. After that, I installed phase loss relays. I also worked with an engineer to calculate arc flash boundaries. We used current limiting devices upstream to reduce energy. These actions were born from experience. They showed me that protection is not just about devices, but about the whole system and the people around it.

Cost and Life Cycle

Upfront cost is one thing. I also look at maintenance cost, downtime, spare parts, and energy efficiency. FSDs are cheaper at high ratings. MCCBs cost more at the start, but I can reset them, and they can lower total cost over time. I compare total cost of ownership for each case.

Counting the Real Costs

In a factory, a fuse blew on a weekend, and we had no spare. The line stayed down for hours. That downtime cost more than the price of an MCCB. In another site, high rating MCCBs were so costly that fuses made sense. I now make a simple table for each project. I list device cost, spare cost, expected trips, and downtime risk. That table guides me more than the sticker price.

Conclusion

Choosing between a fuse switch disconnector and an MCCB depends on fault levels, cost, maintenance, and system needs. I balance speed, adjustability, downtime, and safety. My experience with standards, curves, and coordination helps me decide. Each project is a new mix of these factors. I hope my stories and insights help you in your own decisions.