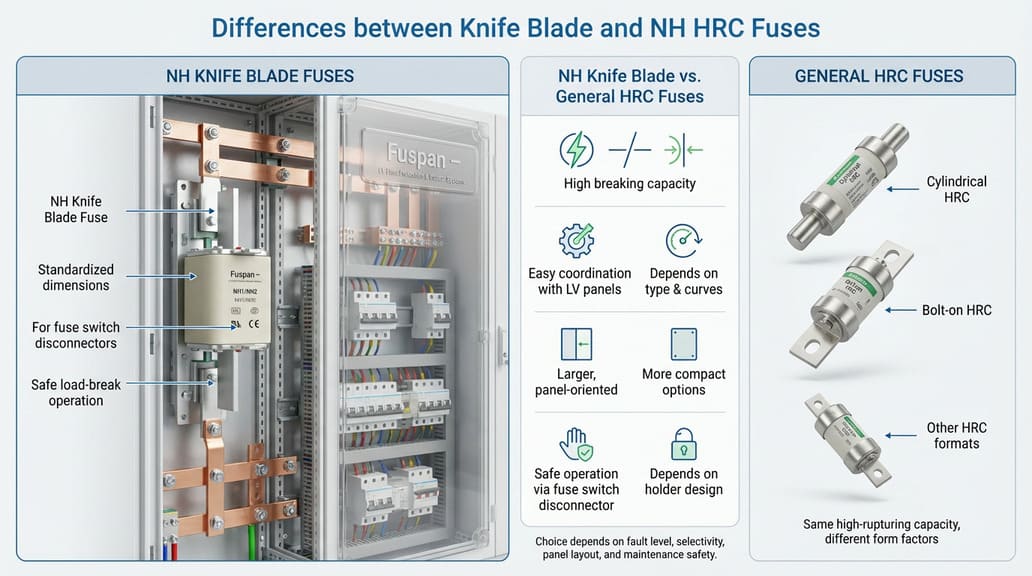

Many customers ask me, “Should I use NH knife blade fuses or general HRC fuses?” They rarely only care about part numbers. They worry about safety, selectivity, and future upgrades.

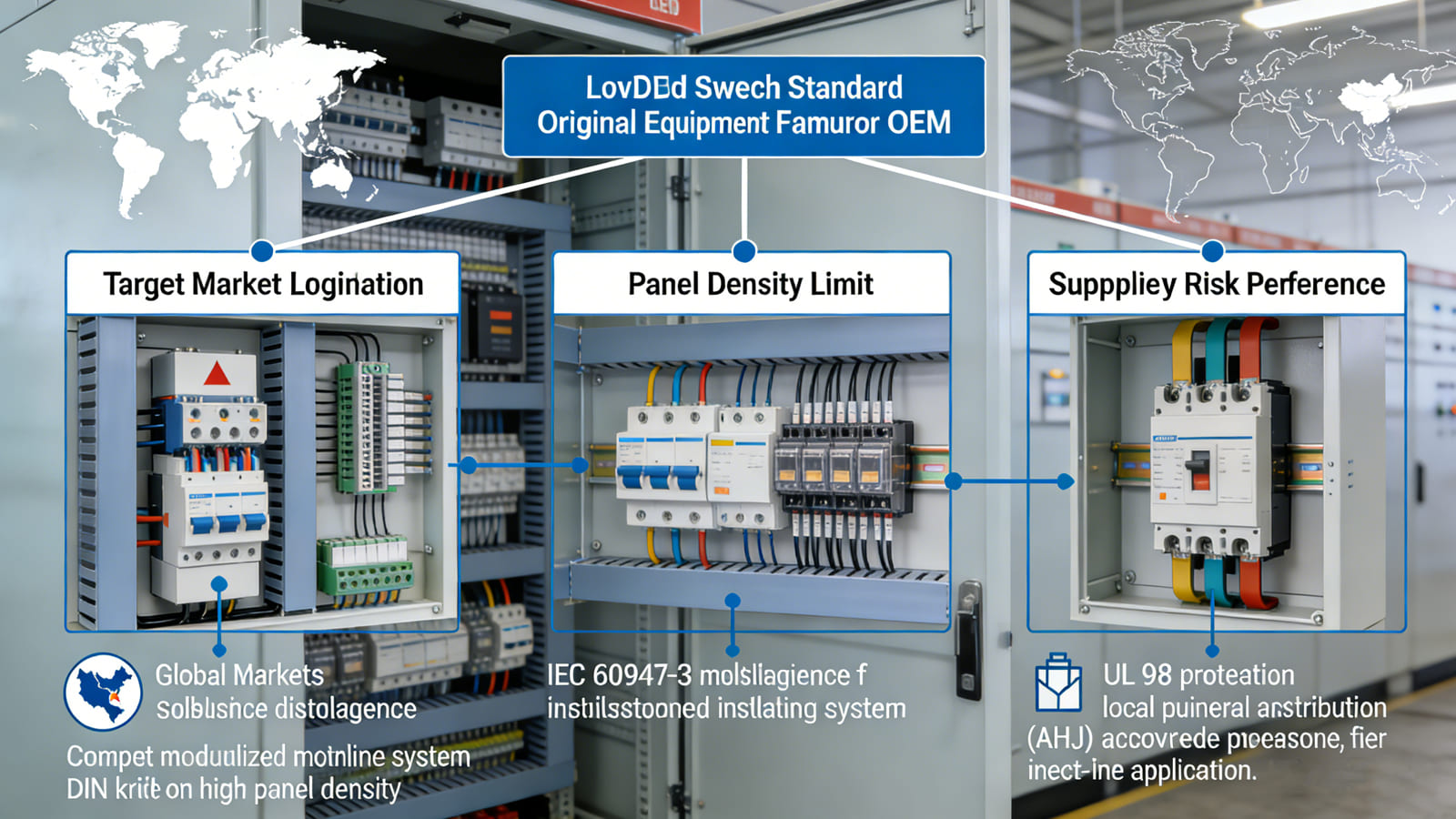

NH knife blade fuses are a specific HRC fuse type with standardized dimensions and knife contacts for use in fuse switch disconnectors, while “general” HRC fuses can include cylindrical, bolt‑on, and other formats. The right choice depends on fault level, selectivity, panel space, and replacement safety.

When I sit down with panel builders, I find that they are not only comparing shapes. They think about whether a technician in a hot, cramped room can replace the fuse safely. They think about how the fuse coordinates with upstream breakers, and if the system can handle higher fault levels in the future. So I like to treat fuse type, breaking capacity, time‑current curves, and replacement procedures as one linked decision. This way, the protection system stays consistent and upgrades are much less painful.

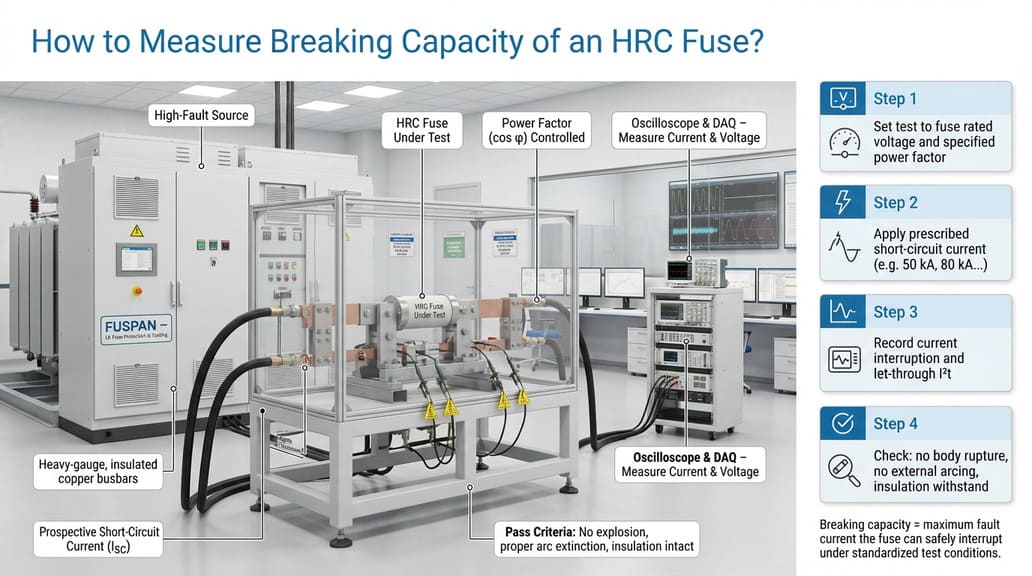

How to measure breaking capacity of an HRC fuse?

Many engineers I meet understand rated current. They know the voltage. But when I ask about breaking capacity, the room goes quiet. Yet this is the number that decides if the fuse will survive a real short circuit.

The breaking capacity of an HRC fuse is determined through high‑fault tests in certified labs, where a prescribed short‑circuit current is applied at rated voltage and power factor, and the fuse must interrupt safely without explosion or loss of insulation.

In practice, I do not measure breaking capacity myself in the field. I rely on type test reports and standards like IEC 60269. Still, I often need to explain what those test numbers mean. If a fuse says “120 kA” breaking capacity, that does not mean we ever want to see 120 kA in real life. It means the fuse proved in the lab that it can clear that fault level without dangerous effects. For many customers, this understanding changes how they select between different fuse classes and body types.

What breaking capacity really tells me

To help customers, I usually break the idea into simple parts.

Basic test idea

In a certified lab, the fuse is placed in a test circuit with:

- Rated system voltage.

- A test power factor defined by the standard.

- A short‑circuit current source set to the target breaking capacity.

The lab applies a fault. The fuse must open the circuit. Then the lab checks:

- Did the fuse clear the current fully?

- Did it stay mechanically safe (no bursting, no ejected parts)?

- Is the insulation distance still safe afterward?

If all is fine, that value becomes the rated breaking capacity.

How I use this in real projects

When I see a project with a known prospective short‑circuit current (for example, 25 kA at the main bus), I check that:

- The HRC fuse breaking capacity is well above that level.

- The associated switch disconnector or base is also rated accordingly.

- The installation method (open base, enclosed box, etc.) matches the test conditions or better.

For NH knife blade fuses, this is often simple because IEC NH sizes come with high breaking capacity, typically 80 kA or more at 400/690 V AC. For some cylindrical or smaller HRC formats, breaking capacity can be lower. This is why I always ask for the actual fault level. If the customer does not know it, I advise them to get a short‑circuit calculation from their system designer before locking in a fuse type.

Comparing NH knife blade and other HRC fuses on breaking capacity

Most NH knife blade fuses that I handle have:

- Very high breaking capacity for LV distribution.

- Clear marking on the body (for example 120 kA at 400 V AC).

- Matching switch fuse bases that are tested together.

Other HRC types, such as some cylindrical fuses, can also offer high breaking capacity, but I see more variation. So when a customer wants to change from NH to another type, I make sure they do not lose safety margins on breaking capacity by accident.

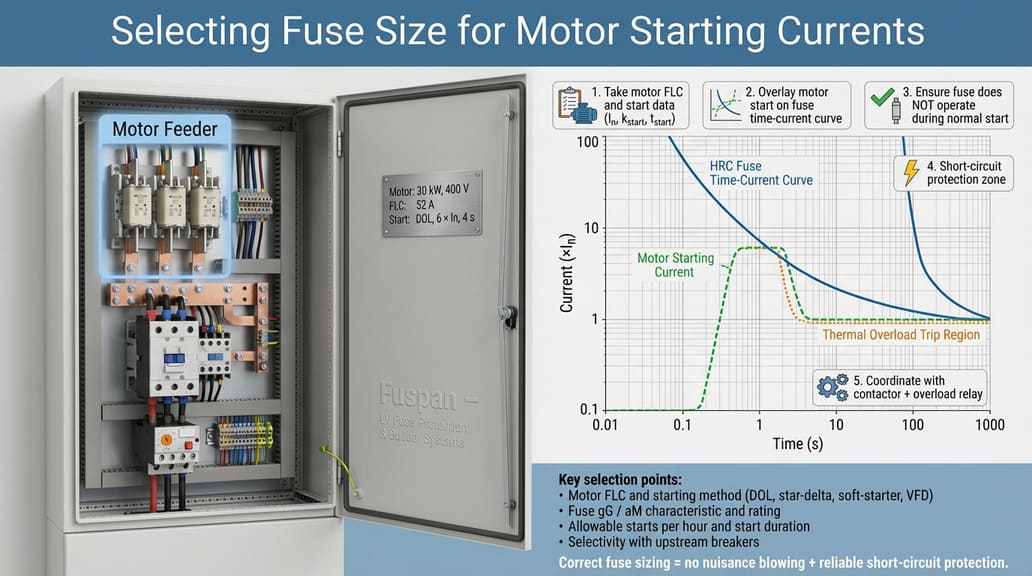

Selecting fuse size for motor starting currents?

Motor circuits give many customers headaches. They see high inrush current on start, nuisance tripping, and confused operators. I hear, “If I size the fuse too big, I lose protection. If I size it too small, it blows during start.”

To select an HRC fuse size for motors, I compare the motor’s full‑load current and starting characteristics with the fuse’s time‑current curve, ensuring the fuse rides through normal starts but clears sustained overloads and short circuits, while coordinating with contactors and breakers.

When I help a customer, I never only look at the motor power in kW. I ask for the rated current on the nameplate, the starting method (DOL, star‑delta, soft starter, VFD), and how often the motor starts. Without this, any sizing is guesswork. Once I have these, I lay the motor starting curve or at least a starting current estimate against the fuse curve. Then I check if the chosen fuse can survive the start without damage and still protect against faults.

Simple way I walk through motor fuse sizing

I try to keep the process practical and step‑by‑step.

1. Find motor current and starting data

I ask the customer for:

- Rated motor current (In_motor).

- Starting method and estimated starting current (often 5–7 × In_motor for DOL).

- Starting time (for example 3–10 seconds).

- Number of starts per hour.

If they do not know exact starting time, I use conservative estimates and add some margin.

2. Choose a fuse utilization category

For motor feeders with NH HRC fuses, I often use gG for cable and general protection or aM for motor protection only, depending on the design:

- gG: full‑range fuse, overload and short‑circuit.

- aM: short‑circuit only, with relay handling overload.

I explain that aM fuses are set higher and rely on a thermal relay to protect the motor. This is very common in motor control centers.

3. Compare currents and curves

Then I:

- Take the motor rated current.

- Apply a factor (for example 1.25–1.6) depending on the utilization category and starting behavior.

- Select a fuse nominal current In_fuse above this value.

- Plot or mentally compare the starting current and time against the fuse time‑current curve.

The fuse must not reach its pre‑arcing or total clearing time at the expected start time. At the same time, for sustained overloads beyond motor protection settings, the system (relay plus fuse) must clear faults without overheating cables or equipment.

4. Check selectivity with upstream devices

I always remind customers that motor fuses do not live alone. We must check:

- Upstream breaker and its trip curve.

- Cable size and allowed I²t.

- Coordination type with contactors (Type 1 or Type 2, according to IEC).

For NH knife blade fuses in fuse switch disconnectors, I often find it easier to achieve Type 2 coordination with standard contactors than with only thermal‑magnetic breakers. This is one reason many panel builders stay with NH systems in motor control centers.

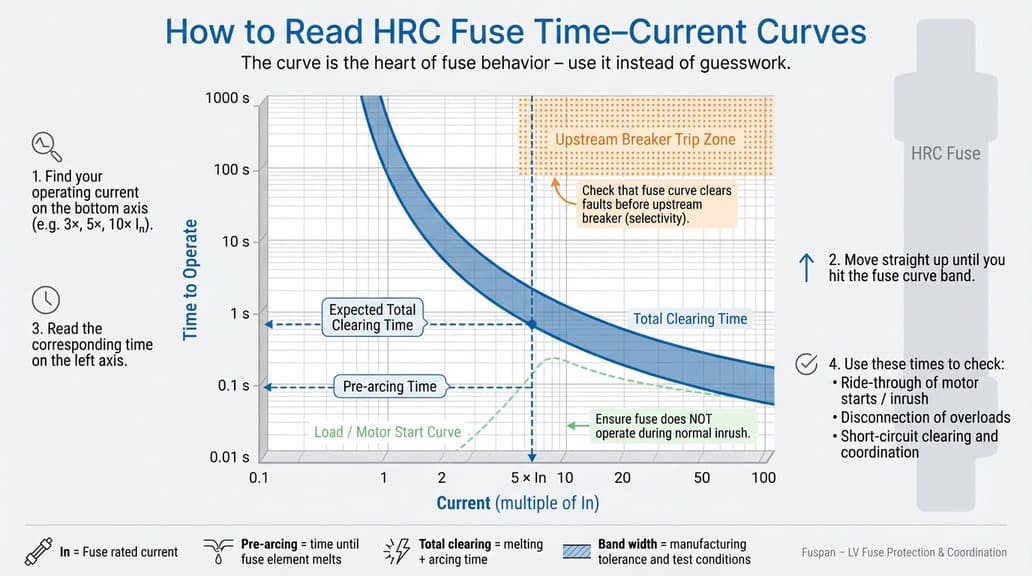

How to read fuse time current curves for HRC fuses?

Many engineers tell me they “do not like graphs.” When they open a fuse data sheet and see a time‑current curve, they close it. But this curve is the heart of fuse behavior. Without it, coordination is guesswork.

To read an HRC fuse time‑current curve, I locate the operating current on the horizontal axis, move up to intersect the fuse curve band, and then read the expected pre‑arcing and total clearing times on the vertical axis, using this to check ride‑through and coordination.

When I guide customers, I often share my screen and walk through a real curve. I show them how the horizontal axis is current in multiples of the fuse rating, and the vertical axis is time, usually on a logarithmic scale. This scare some people at first. Once they see that it is just “higher current means faster operation,” things become much easier.

My simple method for reading and using curves

I like to break it into three short steps and one check.

1. Understand the axes and the band

On a typical curve:

- Horizontal axis: Current, often in multiples of In (rated current) or in amperes.

- Vertical axis: Time, from milliseconds up to hours, on a log scale.

- The curve appears as a band, showing minimum melting (pre‑arcing) and maximum clearing times.

I explain that the lower line shows when the fuse element starts to melt, and the upper line shows when the current is fully interrupted, including arc time.

2. Check normal load and overload

I find the expected normal load current and small overloads on the horizontal axis. Then I go up:

- If the operating point lies below the minimum melting curve, the fuse should not operate.

- If long‑term overload points cross the band, then the fuse will eventually open.

For example, if I size a 100 A fuse and the normal load is 80 A, I confirm that at 80 A the curve indicates “no operation” even over long time. If some overload at 150 A must clear within, say, 10 seconds, I check that the fuse curve crosses near that time.

3. Check short‑circuit behavior

For high fault currents, the times are in milliseconds. I show customers:

- At 10 × In or 20 × In, the fuse clears in a very short time.

- This fast action protects cables and downstream devices from thermal and mechanical stress.

For NH HRC fuses, the let‑through energy (I²t) is often very low compared with breakers. This is one key advantage for coordination.

4. Compare with other curves

The real use of the curve is coordination. I often overlay or mentally compare:

- Fuse curve with upstream breaker curve.

- Fuse curve with downstream device limits.

- Fuse curve with motor or transformer start data.

The goal is to avoid overlap where unwanted devices trip first. For example, I want a feeder fuse to operate before the main breaker for a downstream short circuit. With NH HRC fuses, the clear curve shape makes this coordination easier than with some thermal‑magnetic devices that have less defined behavior at high fault levels.

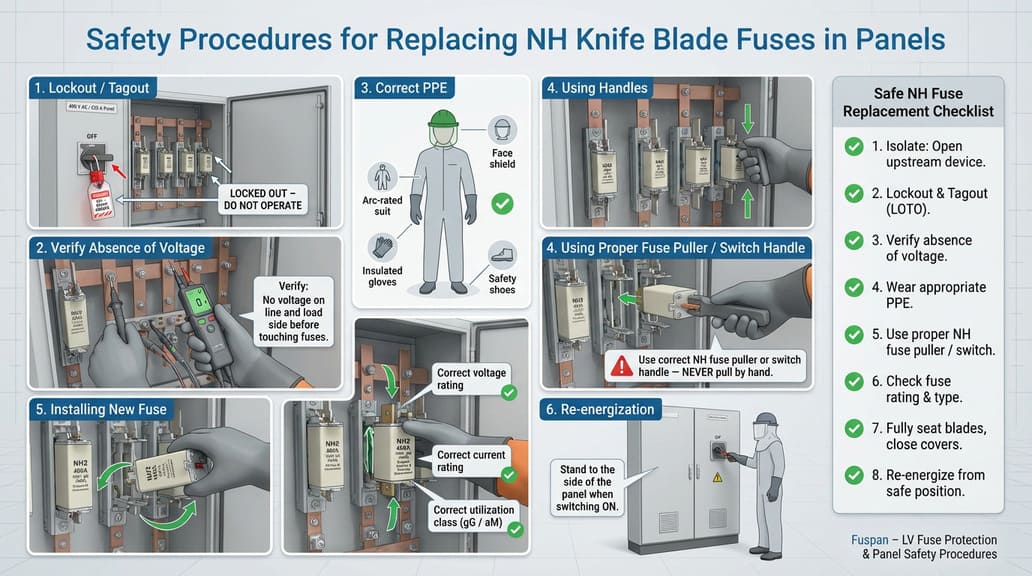

Safety procedures for replacing knife blade fuses in panels?

The most serious problems I see with NH knife blade fuses do not come from the fuses themselves. They come from how people replace them. A good fuse in the wrong hands becomes a risk. So I always stress panel procedures.

To replace NH knife blade fuses safely, I isolate and lock out the circuit, verify absence of voltage, wear appropriate PPE, use a proper fuse puller or switch handle, and follow the panel’s rated operating conditions exactly.

I remember visiting a site where a technician tried to pull an NH fuse from a base while the switch was still energized. He had no face shield, and the panel door was half open. He was lucky that the load was light. This memory stays with me. When I recommend NH fuse switch disconnectors, I always explain that the mechanical design is meant to improve safety, but it does not replace basic procedures.

My typical safety checklist for NH knife blade fuses

I share a simple list with customers and often suggest they put a version on the panel door.

1. Preparation and isolation

Before touching anything:

- Identify the circuit and confirm which fuse you will replace.

- Open the upstream breaker or switch disconnector.

- Apply lockout/tagout according to site rules.

- Wait the specified discharge time if capacitors or drives are present.

I always say, “Do not trust a handle position alone. Verify.”

2. Verify absence of voltage

Using a suitable tester:

- Check test device on a known live source first.

- Test the line and load terminals of the fuse switch or base.

- Test again on the known live source to confirm the tester still works.

Only when all points show zero voltage do I consider the circuit safe to work on.

3. Personal protective equipment (PPE)

Depending on the system and company rules, I advise:

- Insulated gloves.

- Face shield or safety glasses.

- Flame‑resistant clothing if arc risk exists.

- Insulated tools, especially a suitable NH fuse puller if using open bases.

Even on low‑voltage panels, metal tools and rings can cause accidents. I tell technicians to remove jewelry and keep one hand away from live zones when possible.

4. Removing and inserting NH fuses

For NH knife blade fuses, I prefer:

- Using enclosed fuse switch disconnectors with built‑in handles.

- Opening the switch to the OFF position before any access.

- Using the handle to remove and insert fuses, so hands stay outside the live area.

For open fuse bases:

- Use an insulated fuse puller rated for the fuse size.

- Pull straight, avoid twisting that might damage contacts.

- Insert the new fuse fully, ensuring blades are correctly seated.

Loose or partial contact can lead to overheating and future failures.

5. Final checks and re‑energizing

After replacement:

- Visually inspect that all fuses are seated correctly.

- Close covers and doors as required for the panel’s IP and arc classification.

- Remove lockout/tagout in the correct sequence.

- Re‑energize, then monitor the load for a short period for unusual noise, smell, or heat.

I also remind customers to record the replacement. Over time, this helps detect patterns that might point to an underlying design or loading issue rather than “random fuse failures.”

Conclusion

NH knife blade fuses are one specific, highly standardized HRC family. When I match breaking capacity, time‑current curves, motor behavior, and safe replacement practices together, fuse selection and operation in real panels becomes much more reliable.